After the removal of President Nicolás Maduro, the fate of the world’s largest oil reserves has drawn intense scrutiny. Chevron, the lone major U.S. company in Venezuela, has used lobbying and political connections to stay in the game, eyeing a bigger global footprint despite a deeply uncertain environment.

How Chevron played the long game for Venezuela’s oil reserves

Key Takeaways:

- The U.S. invasion removed President Maduro, altering Venezuela’s political future and oil landscape.

- Venezuela holds approximately 300 billion barrels of proven reserves, around 17% of the global total.

- Chevron remained in Venezuela when other majors exited, giving it a strong foothold post-conflict.

- By acquiring Hess, Chevron also secured a stake in neighboring Guyana’s booming offshore fields.

- Enormous debt, battered infrastructure, and political instability pose major hurdles to a quick rebound.

Background on Venezuela’s Oil Abundance

Venezuela boasts an estimated 300 billion barrels of proven oil reserves—roughly 17% of the world’s total. Yet decades of political turmoil and sanctions have kept actual production to a fraction of its potential. “It’s true that they know the oil is there,” said Samantha Gross, director of the Energy Security and Climate Initiative at the Brookings Institution. “But the aboveground risks are huge.”

The U.S. Invasion and Trump’s Statements

On a recent Saturday, U.S. forces in Caracas killed at least 80 people and took then-President Nicolás Maduro into custody. Soon after, Donald Trump vowed that future Venezuelan crude production would be led by “very large United States oil companies,” pumping “a tremendous amount of wealth out of the ground.”

Chevron’s History in Venezuela

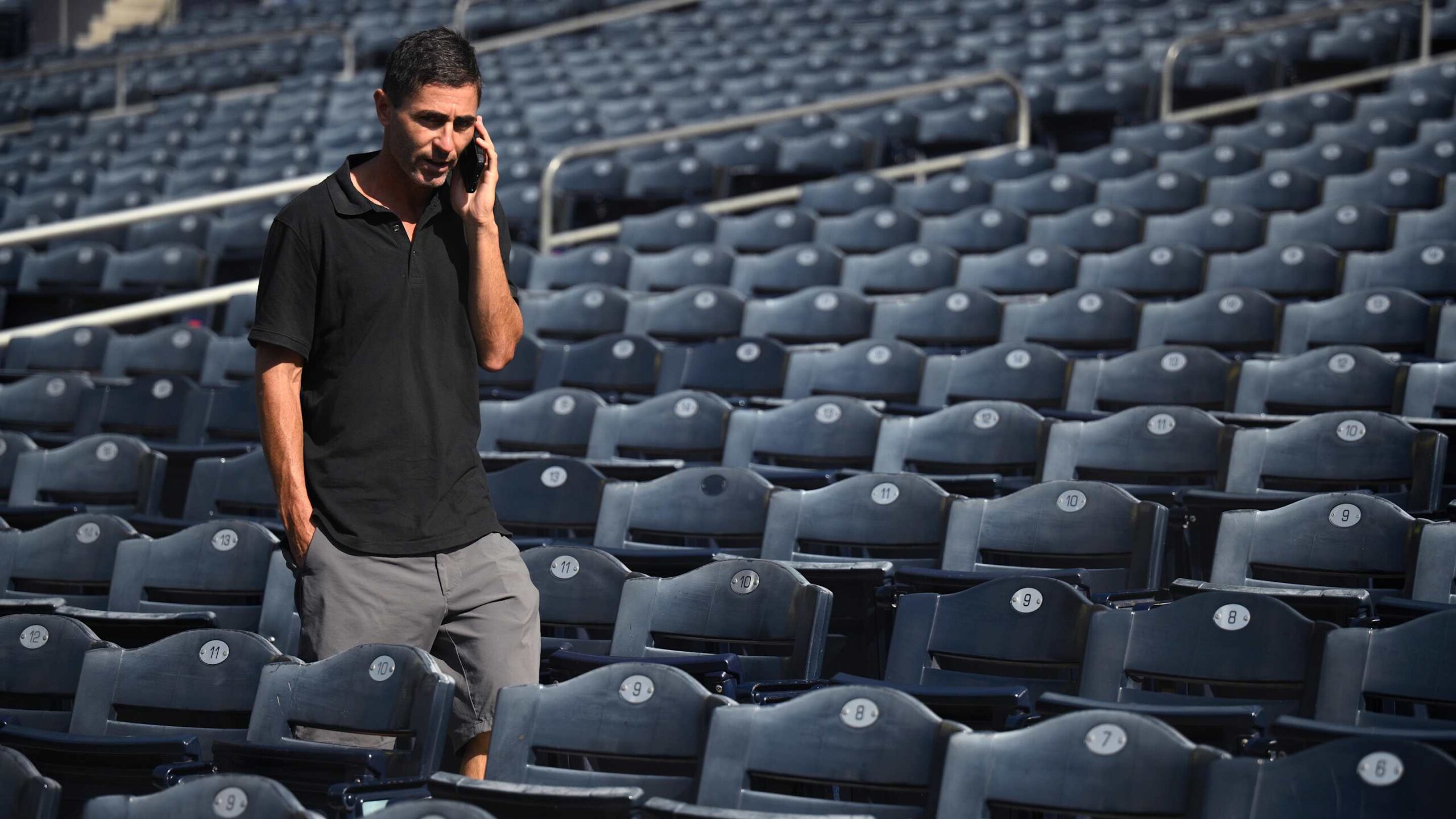

Chevron stands out as the only major U.S. oil firm still operating in Venezuela—a position it has maintained since 2007. When other companies withdrew following the nationalization of the industry by then-President Hugo Chávez, Chevron opted to remain as a minority partner alongside Venezuela’s state oil corporation. “We play a long game,” CEO Mike Wirth said at a U.S.-Saudi investment summit, underscoring how the company preserved infrastructure, personnel, and valuable legal standing.

Lobbying and License Renewal

When President Trump returned to office, he revoked special licenses from the previous administration that allowed Chevron to keep producing despite sanctions. Although initially told to halt operations by April, Chevron continued business as usual. The company spent nearly $4 million on lobbying in the first half of the year, seeking to remain in Venezuela. Behind closed doors, Wirth met with Trump, Secretary of State Marco Rubio, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, and National Security Council staff. By July, the gamble paid off: the administration granted Chevron a new license, allowing it to ramp up production again.

Hess Acquisition and Guyana

Even as it was reestablishing operations in Venezuela, Chevron finalized a $53 billion merger with Hess Corporation. This deal included Hess’s significant stake in Guyana—Venezuela’s neighbor—where massive offshore discoveries have turned global attention to this small nation’s potential. With the merger complete, John Hess joined Chevron’s board.

Challenges Ahead

Political instability and infrastructure woes threaten to slow any rapid rebound in Venezuelan oil. Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) has amassed more than $150 billion in liabilities, and it remains unclear how recovery efforts or new deals might handle these debts. Infrastructure upgrades will require “years and possibly hundreds of billions to bring up to something close to its former capacity,” noted Gus Vasquez of Argus Media.

Meanwhile, global crude prices have been slipping under $60 a barrel—dangerously close to the break-even point for many American producers. Renewable energy’s growth and ongoing uncertainty around international lawsuits further complicate the picture.

Political Fallout

Senate Democrats have opened an investigation into the Trump administration’s dealings with oil companies before the invasion. Questions persist regarding the U.S. plan to sell what Trump calls “sanctioned oil” on the global market, with profits deposited into “U.S.-controlled accounts.” Critics say this arrangement bypasses the U.S. Treasury and leaves Venezuelans with little clarity on how proceeds might be allocated.

Uncertain Future for Venezuelans

Experts such as Cynthia Arson, former director of the Woodrow Wilson International Center’s Latin American Program, question whether Washington’s strategy focuses on restoring democracy and addressing human rights abuses. Even as Chevron and other companies move forward, Venezuelans remain caught between hopes for economic recovery and the realities of social upheaval. “If good things happen, they’re going to take time,” said Samantha Gross. “Bad things could actually happen pretty quickly.”